IGNITING THE FLAME OF UNITY

THE HISTORY OF THE

BRIGHTON BRANCH OF A.S.L.E.F.

"I know no better definition of the rights of man :—Thou shall not steal; Thou shall not be stolen ? What a society were that—

PLATO'S REPUBLIC? MORE'S UTOPIA? mere emblems of it! — THOMAS CARLYLE.

|

|

|

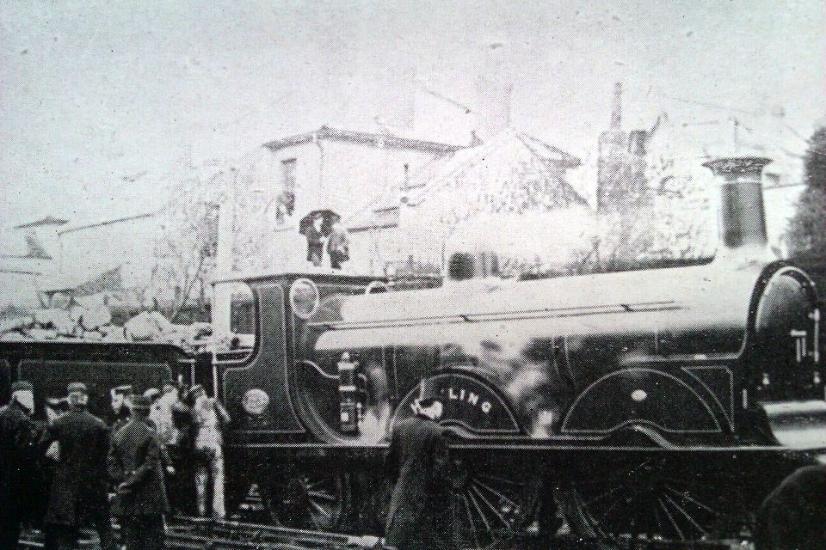

THE COLLAPSE OF PORTLAND ROAD BRIDGE

NORWOOD JUNCTION 1st MAY 1891

EXTACTED AND ADAPTED FROM THE BOARD OF TRADE REPORT

by H.S. Bennett

INVOLVING BRIGHTON ENGINEMEN, DRIVER HARRY HARGREAVES AND HIS FIREMAN JOSEPH GROVER

In this case as the 8.45 a.m. express train from Brighton for London Bridge station was passing at a rapid speed over Portland

Road bridge, the engine, tender, and 12 vehicles composing the train left the rails, the rear vehicle (a brake van) stopping with

its trailing on the south abutment of the bridge, part of the bridge having given way under the passage of train.

One passenger is stated to have had his ankle dislocated, and four other to have been injured; in addition to these complaints of

having been shaken been received from 90 passengers. The driver, fireman, and guards were also shaken.

The train on leaving Brighton consisted of engine and tender No.175, a four wheeled brake van, four six wheeled first class

carriages, two eight wheeled first class bogie carriages, an eight wheel Pullman car, three eight wheeled first class bogie

carriages, two four-wheeled brake-vans, an eight-wheeled first-class bogie-carriage, and a six-wheel first-class carriage, the

whole fitted with the Westinghouse automatic brake ; the rear three vehicles, containing passengers for Victoria, .were slipped

at East Croydon, and at the time of the accident the train consisted, as above stated, of 12 vehicles, each bogie carriage

counting two ordinary vehicles.

The train, although at a running at a speed of probably at least 40 miles an hour, stopped in about its own length (about 190

yards), in the position shown in the diagram. The vehicle all remained upright or nearly so, and close together, with the

exception of gaps between the leading brake-van and carriage next it, and between the last two bogie-carriages. The most

serious damage was sustained by the rear compartment of the first of these two bogie-carriages ; its trailing bogie was pushed

back to the rear of the carriage, and remained with its trailing wheels on the top of the north abutment of the bridge. The rear

brake-van remained suspended over Portland Road with its front end coupled to the carriage in front, and its trailing wheels

resting on the southern abutment of the bridge. The rails over the bridge did not give way, but remained in festoons, the front

wheels of the brake-van resting lightly on them.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Description.

On Portland Road bridge, a short distance on the north aide of Norwood Junction station, there are seven lines of rails, of

which four are running lines and three are sidings. The lines in the immediate neighbourhood are straight and practically level.

The up and down main lines are together near the centre of the bridge, the up lines being of the up main line, and the down

local line to the east of the down line. The bridge was originally constructed by the London Croydon Railway Company with a

span of 20 feet, the girders being then cast iron trough girders; it was enlarged for an additional line of rails in 1852, the span

remaining the same. In 1859, when the line had become the property of the present Company, the bridge was reconstructed in

connection with the erection of the existing Norwood Junction station, its span being increased to 25 feet on the square or 26 ¾

feet on the skew, and it being made to carry seven lines rails. Each line of rails is supported by cross girders, each cross girder

being formed of two rails bolted together but separated by a shaped baulk placed between them, making their depth about 5

inches and breadth about 8 inches.

Evidence

Harry Hargreaves, driver; 22 years’ service, 14 years driver. I have been employed as express driver for about 7 years. I booked on duty on May 1st at 8 a.m. to sign off at 4 p.m. On leaving Brighton at 8.45 a.m. my train consisted of engine and tender

(“Hayling”) and 15 vehicles counting as 22. My engine was a six wheeled engine, four wheels (leading and driving) coupled,

and a six wheeled tender. The Westinghouse brake fitted throughout the train, except to the centre wheels of four six wheeled

coaches. I work the brake at a pressure of 75lbs. for the engine and tender and 60 lbs. for the train. We left Brighton punctually,

and the only signals against me were at the south end of East Croydon, but they were taken off after passing the distant signal. I

had shut off steam before reaching East Croydon, but ran through the station with steam on at a speed of about 40 miles an

hour. The three rear vehicles for Victoria were slipped as usual before reaching East Croydon I found no signals against me,

and my speed at the Portland Road bridge was not more than 35 to 40 miles an hour, 14 minutes being allowed for the 8 ½

miles between Norwood junction and London Bridge. Just as the engine got on to Portland Road bridge. I felt a jerk, and I think

that both engine and tender had cleared the bridge when I felt the engine take to the right towards the 6ft. space between the up

and down main lines. I was nearly thrown down by the jump of the engine in leaving the rails, but I kept myself from falling by

catching hold of the reversing wheel on the left side of the engine. I then seized the Westinghouse brake regulator and applied

the brake with full force, and then shut off steam. I am sure that my application of the brake was before it had been

automatically applied. It was about opposite the signal cabin when I got the brake on. The stoppage of the engine occurred

gradually. Both I and the fireman remained on the footplate. I have been shaken, but have not had to go on the sick list, I heard

no noise anything like an explosion when the accident occurred. I am not all deaf. I was running to time when the accident

occurred.

Joseph Grover, fireman; 14 years’ service, 11 years fireman. I have been Hargeaves’ fireman for about two years, and I was with him on May 1st, as fireman of the 8.45 a.m. up express from Brighton. My place on the footplate is on the 6ft. side. The only

signals against us were those on the south side of East Croydon, but here the home signal was taken off before we reached it, the

train having been previously slacked. The slip was made all right at East Croydon, and I think the speed at Portland Road

bridge was 40 miles an hour. I was looking out on my side when we came to the bridge; the first thing I felt was the engine jump

when the leading wheels had reached the London side of the bridge. After this the wheels all left the rails, and we stopped in

about the train’s length. The driver first put on the brake and then shut off steam. I went to the hand brake, but was knocked

down on the footplate. I got up and held on to the brake pillar till we stopped. I was shaken, but have not to leave work. I hear

no loud noise like a fog signal exploding just as the accident occurred.

Mark Sayers, guard; 13 years’ service, 12 years guard. I came on duty at 5.15 a.m. on May 1st, to sign off at 6.30 p.m., being

unemployed between 10 a.m. and 2 a.m. I was in charge of the 8.45 a.m. up express from Brighton. It left punctually, consisting

of engine, tender, brake van (in which I was riding), the four six wheeled first class coaches, two bogie first class, one Pullman

car, three bogie first class, brake van in which guard Hunt was riding, brake van, bogie first class, and first class carriage, each

bogie carriage and the Pullman car counting as two – the train being therefore equivalent to one of 22 vehicles. The three rear

vehicles were slipped for Victoria at East Croydon, where I noticed that we were checked by signals, this being the only check

which I observed. As we approached Norwood north cabin I was looking out on the left hand side; the speed was about 35 and

40 miles an hour, and just as the engine was on or just over the bridge I saw it lurch and leave the rails, my van following it and

pitching me from the left to the right hand side. I was stunned, and on recovering myself when the train had stopped, I was on

the floor on the right hand side of the van with a piece of rail sticking through the floor of the van near the front, and another

through the floor the front, and left hand side near the rear. I was hurt in the head and the face. I heard no noise like that of an

explosion when the accident occurred. The train was not full, there not being more than 200 passengers, much fewer as usual.

Frederick Hunt, guard; 23 year’s service, 18 years guard. I commenced work at the same time as Sayers, at about 5.15 a.m., to sign off at 1.5 p.m. on May 1st I was rear guard of the 8.45 a.m. up express after it passed East Croydon, where the rear three

vehicles had been slipped. Westinghouse inspector Constable was with me in the van, I was sitting on the left side of the van as

we approached Norwood north, and looking through the side light, and the first thing I felt was being thrown from my seat, and

then a series of shocks like what would occur from a sudden application, either automatic or otherwise, of the brake. The van

then stopped with its leading end attached to the bogie in front, and the rear wheels on the south abutment of the bridge. The

rails were still across the gap the off rail turned on its side; there was an open space underneath. The van afterwards dropped

into gap, in endeavouring to draw from behind. I was not hurt, nor was Constable. The speed was about 40 miles an hour.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

James Sawyers, signalman; 30 years’ service, all the time signalman. I have been employed 21 ½ at Norwood north cabin, where I came on duty at 6.15 a.m. on May 1st to remain till 2 p.m. I have a booking boy to assist me, and he was in the cabin at

the time of the accident. The train which next preceded the 8.45 a.m. up express was the South Eastern train due to leave Redhill

at 9.16 a.m., and it passed my cabin at 9.34 a.m., pretty well on time. It passed at the ordinary speed of about 40 miles an hour.

I heard nothing unusual in the way of noise or otherwise as this train passed over the bridge. I did not happen to look down at

the bridge after the train had passed. The first signal I received for the 8.45 a.m. up train was from Norwood south junction

(about a quarter of a mile distant) at 9.36 a.m. I was able to accept it I received “Train on line” for the express at 9.40 a.m., my

up home and distant signals being already lowered. The train reached the bridge at about 9.41 a.m., and was approaching at its

usual speed with signals off, quite 40 miles an hour, when I heard a loud report like a cannon exploding I was near the south

end of the cabin at the time, but not looking southward, until I heard the report, and then on looking down I saw that there was a

hole in the bridge on the west side, from which the woodwork had all gone, and I heard from the noise of scrunching and

grinding that the train was of the rails. I at once threw the starting signal against the up local train which was ready to start. I

then blocked the down main line to Anerley with sex beats having received a “Be ready” from Anerley at 9.40 a.m. just about

time the noise occurred. Before accepting the “Be ready” I blocked the line, and also the main up line to the Norwood south.

Seeing that the down local line was apparently clear, I allowed a down local train to come as far as the down stop signal and on

hearing from the outside that this line was clear, I let the train come on. I notice after the train stopped that the rear brake van

was hanging over the gap, suspended by coupling to the carriage in front of it.

Charles Tee; train signal clerk; 13 months’ service, train signal clerk all the time. I have been nine months at Norwood north cabin, where I came on duty at 7 a.m. on May 1st for 12 hours. I make entries in the train book. The train which passed on the

up main line next before the up express was a South eastern passenger train at 9.34. a.m. I noticed nothing unusual as this train

passed, either as regards noise otherwise. At 9.36 a.m. the “Be ready” for the 8.45 a.m. express was given on from Norwood

south at 9.40 a.m., and the accident occurred between 9.40 and 9.41 a.m. I was not watching the train as it approached, but I

heard a loud noise like a gun going off just as the engine reached the bridge. On hearing the noise I looked towards London and

saw the engine and the rest of the train of the train off the rails, and stopping, and they came to stand while I was looking at

them, with the rear guard’s van hanging over the Portland Road bridge. The train was running at about the same speed as

usual. The “Be ready” for a down main line train had been received just when the noise occurred, and Sawyers, instead of

accepting the signal, blocked the road, and I saw him also throw up the starting signal against the up local train. There was a

signal clerk in training in the cabin at the time. He was at the time of the accident at the speaking instrument. I did not notice

any permanent way men near the bridge at the time of the accident.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Conclusion

There is no doubt but this very serious accident was caused by the failure of a cast iron girder, the west one of the two which

carried the up main line over Portland Road. Whether the girder was broken by the passage of the previous train (belong to the

South Eastern Company) about six minutes before the express train which met with the accident or by the engine of the train

itself, it is difficulty to say. Neither the driver nor the guard of the South Eastern train observed anything unusual as they passed

over the bridge; but Hargreaves, the driver of the up express train who gave his evidence in a very clear, straightforward

manner states that he felt a jerk as his engine got on to the bridge, and that then both engine and tender left the rails as soon as

they cleared the bridge, first inclining to the right and then stopping gradually. Hargreaves was nearly thrown down when the

engine left the rails butt managed to seize hold of the Westinghouse brake regulator and applying the brake with full force as his

engine was passing the signal cabin about 20 yards on the north side of the bridge, and then shut off steam. He estimates the

speed at not more than 40 miles an hour at the bridge.

Driver Hargreaves fireman Grover, gives evidence of a similar character. He was knocked down on the footplate when the

engine left the rails, but got up and held on by the brake pillar till his engine stopped.

Guard Sayers, in the brake van next the tender, saw the engine lurch and leave the rails just as it reached the bridge, when the

speed was between 35 and 40 miles an hour. The brake van followed the tender off the rails, Sayers being thrown down and

stunned. On coming to himself when his van had stopped he found a piece of rail sticking up through the floor of the van near

the front, and another through the floor near the rear end.

Hunt, the guard in the rear brake van, was thrown from his seat and felt a series of shocks (such as would occur from a sudden

application of the Westinghouse brake, and from the front of the train having left the rails) as they were approaching Norwood

north cabin, the speed being about 40 miles an hour. Hunt speaks as to the position of the van remaining suspended across the

gap caused by the collapse of the bridge, the rails hanging in festoons below it.

The signalman and an assistant in Norwood north cabin (which is built on supports, over the up local line about 20 yards north

of Portland Road bridge) both speak of to a loud noise like an explosion just as the engine passed the bridge (this noise, which

was not heard by either driver, fireman, or guards, was probably caused by the fall of the corrugated iron, fixed to the under

side of the bridge, on the road beneath). The signal man on seeing what had occurred at once threw the starting signal against

the up local train which was ready to start (part of the express being across the up local line), blocked both, up and down main

lines, and stopped a train on the down local line until he has ascertained that that line was clear.

The cast iron girder which failed on this occasion, causing the floor of the bridge to give way, and the wheels of the engine and

tender, and then of all the succeeding vehicles in the train to leave the rails, had been in its place on the west side of the up main

line for about 31 years, and during the whole of this time had had concealed in the interior of the web and in the outer part of

the flawnge a very serious flaw, abstracting at least one fourth from the strength of the girder. As before stated this flaw was

invisible when the girder was cast, owing to the practice of using sheet iron in the foundry operations at special parts of the

casting, such as gussets.

Independent, however, of the flaw in this girder, it did not possess a sufficient theoretical margin of safety for passage of the

engines now in use on the line. Its calculated breaking weight at the centre, supposing the bottom flange to be perfect, not

exceeding 71 tons, whereas for the engine drawing the express train this breaking weight should have been at least 83 tons, and

more for other engine s running on the same line.

The attention of the Brighton Company was drawn by the Board of Trade to this deficiency of strength after the occurrence of

the accident on this bridge in December 1876, when two identical girders at a different part of the same bridge were broken by

an engine getting of the rails, and they were then recommended to substitute stronger girders in place, a recommendation to

which unfortunately no attention was paid, or the present serious accident would have been prevented; the Brighton Company

is therefore, in my opinion deserving of much blame for having omitted to substitute stronger girders for existing one after

attention had been thus specially directed to the weakness of the latter.

It is satisfactory to be able, on the other hand, to express the opinion that it was owning to the nature, and the strength of the

vehicles composing the express train, and to the prompt application of the Westinghouse brake by driver Hargreaves, that so

comparatively little personal injury or damaged to rolling stock was sustained. Signalman Sawyers, on duty in Norwood north

cabin, also acted with commendable promptitude in at once blocking both up local and down main lines on seeing that the up

express had fouled them.

Shortly before the accident an arrangement had been come between the Corporation of Croydon and the Brighton Company to

widen Portland Road bridge and increase its span from 26 ¾ to 42 feet; the work will now be immediately commenced, and

mean time the existing girders have been supported in the middle by timber uprights under the bottom flanges.

The chief engineer of the Company informs me that there are only five cast iron girder under bridges now existing on the man

line between London and Brighton and I trust that in view of the very serious accident no unnecessary time will be lost.

On Portland Road bridge, a short distance on the north aide of Norwood Junction station, there are seven lines of rails, of which four are running lines and three are sidings. The lines in the immediate neighbourhood are straight and practically level. The up and down main lines are together near the centre of the bridge, the up lines being of the up main line, and the down local line to the east of the down line. The bridge was originally constructed by the London Croydon Railway Company with a span of 20 feet, the girders being then cast iron trough girders; it was enlarged for an additional line of rails in 1852, the span remaining the same. In 1859, when the line had become the property of the present Company, the bridge was reconstructed in connection with the erection of the existing Norwood Junction station, its span being increased to 25 feet on the square or 26 ¾ feet on the skew, and it being made to carry seven lines rails. Each line of rails is supported by cross girders, each cross girder being formed of two rails bolted together but separated by a shaped baulk placed between them, making their depth about 5 inches and breadth about 8 inches.

Evidence

James Sawyers, signalman; 30 years’ service, all the time signalman. I have been employed 21 ½ at Norwood north cabin, where I came on duty at 6.15 a.m. on May 1st to remain till 2 p.m. I have a booking boy to assist me, and he was in the cabin at the time of the accident. The train which next preceded the 8.45 a.m. up express was the South Eastern train due to leave Redhill at 9.16 a.m., and it passed my cabin at 9.34 a.m., pretty well on time. It passed at the ordinary speed of about 40 miles an hour. I heard nothing unusual in the way of noise or otherwise as this train passed over the bridge. I did not happen to look down at the bridge after the train had passed. The first signal I received for the 8.45 a.m. up train was from Norwood south junction (about a quarter of a mile distant) at 9.36 a.m. I was able to accept it I received “Train on line” for the express at 9.40 a.m., my up home and distant signals being already lowered. The train reached the bridge at about 9.41 a.m., and was approaching at its usual speed with signals off, quite 40 miles an hour, when I heard a loud report like a cannon exploding I was near the south end of the cabin at the time, but not looking southward, until I heard the report, and then on looking down I saw that there was a hole in the bridge on the west side, from which the woodwork had all gone, and I heard from the noise of scrunching and grinding that the train was of the rails. I at once threw the starting signal against the up local train which was ready to start. I then blocked the down main line to Anerley with sex beats having received a “Be ready” from Anerley at 9.40 a.m. just about time the noise occurred. Before accepting the “Be ready” I blocked the line, and also the main up line to the Norwood south. Seeing that the down local line was apparently clear, I allowed a down local train to come as far as the down stop signal and on hearing from the outside that this line was clear, I let the train come on. I notice after the train stopped that the rear brake van was hanging over the gap, suspended by coupling to the carriage in front of it.

Charles Tee; train signal clerk; 13 months’ service, train signal clerk all the time. I have been nine months at Norwood north cabin, where I came on duty at 7 a.m. on May 1st for 12 hours. I make entries in the train book. The train which passed on the up main line next before the up express was a South eastern passenger train at 9.34. a.m. I noticed nothing unusual as this train passed, either as regards noise otherwise. At 9.36 a.m. the “Be ready” for the 8.45 a.m. express was given on from Norwood south at 9.40 a.m., and the accident occurred between 9.40 and 9.41 a.m. I was not watching the train as it approached, but I heard a loud noise like a gun going off just as the engine reached the bridge. On hearing the noise I looked towards London and saw the engine and the rest of the train of the train off the rails, and stopping, and they came to stand while I was looking at them, with the rear guard’s van hanging over the Portland Road bridge. The train was running at about the same speed as usual. The “Be ready” for a down main line train had been received just when the noise occurred, and Sawyers, instead of accepting the signal, blocked the road, and I saw him also throw up the starting signal against the up local train. There was a signal clerk in training in the cabin at the time. He was at the time of the accident at the speaking instrument. I did not notice any permanent way men near the bridge at the time of the accident.

On the 1st May, 1891 the 8.45 a.m. Brighton to London Bridge Pullman Car express being worked by Brighton driver Harry Hargreaves and his fireman Joseph Grover. At East Croydon after slipping the last three vehicles for Victoria. A few minutes later the train passed through Norwood Junction and was approaching the cast iron bridge over Portland Road, when Brighton driver Harry Hargreaves noticed the ballast ahead was disarranged. Being unable to stop in time and realising that all was not well with the bridge, Harry Hargreaves opened the regulator fully, rushed across and then braked hard as his engine a 'Gladstone Class' No. 175 Hayling left the rails and ploughed its way along the ballast, followed by all twelve carriages. The bridge had been fractured by a previous train, and after the 8.45 a.m. express had stopped the rear van fell through the broken span and came to rest on end in the road |  |

way. Five passengers were injured and another ninety complained of shock and minor bruising. At the subsequent inquiry it was stated that the bridge had been built by the London & Croydon Railway of cast iron girders and had a span of 20 feet. It had been enlarged in 1852 and in 1859 reconstructed. The metal was badly corroded and some of the fractures had been present for some years.

Harry Hargreaves, driver; 22 years’ service, 14 years driver. I have been employed as express driver for about 7 years. I booked on duty on May 1st at 8 a.m. to sign off at 4 p.m. On leaving Brighton at 8.45 a.m. my train consisted of engine and tender ( a 'Gladstone Class' No 175 “Hayling”) and 15 vehicles counting as 22. My engine was a six wheeled engine, four wheels (leading and driving) coupled, and a six wheeled tender. The Westinghouse brake fitted throughout the train, except to the centre wheels of four six wheeled coaches. I work the brake at a pressure of 75lbs. for the engine and tender and 60 lbs. for the train. We left Brighton punctually, and the only signals against me were at the south end of East Croydon, but they were taken off after passing the distant signal. I had shut off steam before reaching East Croydon, but ran through the station with steam on at a speed of about 40 miles an hour. The three rear vehicles for Victoria were slipped as usual before reaching East Croydon I found no signals against me, and my speed at the Portland Road bridge was not more than 35 to 40 miles an hour, 14 minutes being allowed for the 8 ½ miles between Norwood junction and London Bridge. Just as the engine got on to Portland Road bridge. I felt a jerk, and I think that both engine and tender had cleared the bridge when I felt the engine take to the right towards the 6ft. space between the up and down main lines. I was nearly thrown down by the jump of the engine in leaving the rails, but I kept myself from falling by catching hold of the reversing wheel on the left side of the engine. I then seized the Westinghouse brake regulator and applied the brake with full force, and then shut off steam. I am sure that my application of the brake was before it had been automatically applied. It was about opposite the signal cabin when I got the brake on. The stoppage of the engine occurred gradually. Both I and the fireman remained on the footplate. I have been shaken, but have not had to go on the sick list, I heard no noise anything like an explosion when the accident occurred. I am not all deaf. I was running to time when the accident occurred.

Joseph Grover, fireman; 14 years’ service, 11 years fireman. I have been Hargeaves’ fireman for about two years, and I was with him on May 1st, as fireman of the 8.45 a.m. up express from Brighton. My place on the footplate is on the 6ft. side. The only signals against us were those on the south side of East Croydon, but here the home signal was taken off before we reached it, the train having been previously slacked. The slip was made all right at East Croydon, and I think the speed at Portland Road bridge was 40 miles an hour. I was looking out on my side when we came to the bridge; the first thing I felt was the engine jump when the leading wheels had reached the London side of the bridge. After this the wheels all left the rails, and we stopped in about the train’s length. The driver first put on the brake and then shut off steam. I went to the hand brake, but was knocked down on the footplate. I got up and held on to the brake pillar till we stopped. I was shaken, but have not to leave work. I hear no loud noise like a fog signal exploding just as the accident occurred

Mark Sayers, guard; 13 years’ service, 12 years guard. I came on duty at 5.15 a.m. on May 1st, to sign off at 6.30 p.m., being unemployed between 10 a.m. and 2 a.m. I was in charge of the 8.45 a.m. up express from Brighton. It left punctually, consisting of engine, tender, brake van (in which I was riding), the four six wheeled first class coaches, two bogie first class, one Pullman car, three bogie first class, brake van in which guard Hunt was riding, brake van, bogie first class, and first class carriage, each bogie carriage and the Pullman car counting as two – the train being therefore equivalent to one of 22 vehicles. The three rear vehicles were slipped for Victoria at East Croydon, where I noticed that we were checked by signals, this being the only check which I observed. As we approached Norwood north cabin I was looking out on the left hand side; the speed was about 35 and 40 miles an hour, and just as the engine was on or just over the bridge I saw it lurch and leave the rails, my van following it and pitching me from the left to the right hand side. I was stunned, and on recovering myself when the train had stopped, I was on the floor on the right hand side of the van with a piece of rail sticking through the floor of the van near the front, and another through the floor the front, and left hand side near the rear. I was hurt in the head and the face. I heard no noise like that of an explosion when the accident occurred. The train was not full, there not being more than 200 passengers, much fewer as usual.

Frederick Hunt, guard; 23 year’s service, 18 years guard. I commenced work at the same time as Sayers, at about 5.15 a.m., to sign off at 1.5 p.m. on May 1st I was rear guard of the 8.45 a.m. up express after it passed East Croydon, where the rear three vehicles had been slipped. Westinghouse inspector Constable was with me in the van, I was sitting on the left side of the van as we approached Norwood north, and looking through the side light, and the first thing I felt was being thrown from my seat, and then a series of shocks like what would occur from a sudden application, either automatic or otherwise, of the brake. The van then stopped with its leading end attached to the bogie in front, and the rear wheels on the south abutment of the bridge. The rails were still across the gap the off rail turned on its side; there was an open space underneath. The van afterwards dropped into gap, in endeavouring to draw from behind. I was not hurt, nor was Constable. The speed was about 40 miles an hour.

Conclusion

There is no doubt but this very serious accident was caused by the failure of a cast iron girder, the west one of the two which carried the up main line over Portland Road. Whether the girder was broken by the passage of the previous train (belong to the South Eastern Company) about six minutes before the express train which met with the accident or by the engine of the train itself, it is difficulty to say. Neither the driver nor the guard of the South Eastern train observed anything unusual as they passed over the bridge; but Hargreaves, the driver of the up express train who gave his evidence in a very clear, straightforward manner states that he felt a jerk as his engine got on to the bridge, and that then both engine and tender left the rails as soon as they cleared the bridge, first inclining to the right and then stopping gradually. Hargreaves was nearly thrown down when the engine left the rails butt managed to seize hold of the Westinghouse brake regulator and applying the brake with full force as his engine was passing the signal cabin about 20 yards on the north side of the bridge, and then shut off steam. He estimates the speed at not more than 40 miles an hour at the bridge.

Hargreaves fireman Grover, gives evidence of a similar character. He was knocked down on the footplate when the engine left the rails, but got up and held on by the brake pillar till his engine stopped.

Guard Sayers, in the brake van next the tender, saw the engine lurch and leave the rails just as it reached the bridge, when the speed was between 35 and 40 miles an hour. The brake van followed the tender off the rails, Sayers being thrown down and stunned. On coming to himself when his van had stopped he found a piece of rail sticking up through the floor of the van near the front, and another through the floor near the rear end.

Hunt, the guard in the rear brake van, was thrown from his seat and felt a series of shocks (such as would occur from a sudden application of the Westinghouse brake, and from the front of the train having left the rails) as they were approaching Norwood north cabin, the speed being about 40 miles an hour. Hunt speaks as to the position of the van remaining suspended across the gap caused by the collapse of the bridge, the rails hanging in festoons below it.

The signalman and an assistant in Norwood north cabin (which is built on supports, over the up local line about 20 yards north of Portland Road bridge) both speak of to a loud noise like an explosion just as the engine passed the bridge (this noise, which was not heard by either driver, fireman, or guards, was probably caused by the fall of the corrugated iron, fixed to the under side of the bridge, on the road beneath). The signal man on seeing what had occurred at once threw the starting signal against the up local train which was ready to start (part of the express being across the up local line), blocked both, up and down main lines, and stopped a train on the down local line until he has ascertained that that line was clear.

The cast iron girder which failed on this occasion, causing the floor of the bridge to give way, and the wheels of the engine and tender, and then of all the succeeding vehicles in the train to leave the rails, had been in its place on the west side of the up main line for abot 31 years, and during the whole of this time had had concealed in the interior of the web and in the outer part of the flawnge a very serious flaw, abstracting at least one fourth from the strength of the girder. As before stated this flaw was invisible when the girder was cast, owing to the practice of using sheet iron in the foundry operations at special parts of the casting, such as gussets.

Independent, however, of the flaw in this girder, it did not possess a sufficient theoretical margin of safety for passage of the engines now in use on the line. Its calculated breaking weight at the centre, supposing the bottom flange to be perfect, not exceeding 71 tons, whereas for the engine drawing the express train this breaking weight should have been at least 83 tons, and more for other engine s running on the same line.

The attention of the Brighton Company was drawn by the Board of Trade to this deficiency of strength after the occurrence of the accident on this bridge in December 1876, when two identical girders at a different part of the same bridge were broken by an engine getting of the rails, and they were then recommended to substitute stronger girders in place, a recommendation to which unfortunately no attention was paid, or the present serious accident would have been prevented; the Brighton Company is therefore, in my opinion deserving of much blame for having omitted to substitute stronger girders for existing one after attention had been thus specially directed to the weakness of the latter.

It is satisfactory to be able, on the other hand, to express the opinion that it was owning to the nature, and the strength of the vehicles composing the express train, and to the prompt application of the Westinghouse brake by driver Hargreaves, that so comparatively little personal injury or damaged to rolling stock was sustained. Signalman Sawyers, on duty in Norwood north cabin, also acted with commendable promptitude in at once blocking both up local and down main lines on seeing that the up express had fouled them.

Shortly before the accident an arrangement had been come between the Corporation of Croydon and the Brighton Company to widen Portland Road bridge and increase its span from 26 ¾ to 42 feet; the work will now be immediately commenced, and meantime the existing girders have been supported in the middle by timber uprights under the bottom flanges.

The chief engineer of the Company informs me that there are only five cast iron girder under bridges now existing on the man line between London and Brighton and I trust that in view of the very serious accident no unnecessary time will be lost.