THIS WEBSITE, THE BRIGHTON BRANCH OF A.S.L.E.&F.

HAS NOW BEEN MOVED TO A NEW SITE CALLED

IGNITING THE FLAMING OF UNITY

http://ignitingtheflameofunity.yolasite.com/1883.php

PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW TO TRANSFER TO THIS NEW SITE

CLICK ON THE ABOVE IMAGE TO TAKE YOU

TO THE NEW UPDATED COMBINED AND WEBSITE

IGNITING THE FLAME OF UNITY WEBSITE

THIS WEBSITE COMBINES THE FOLLOWING WEBSITES

THE BRIGHTON A.S.L.E.&F., THE BRIGHTON MOTIVE POWER DEPOTS

& THE SUSSEX MOTIVE POWER WEBSITES

WHICH EXPLAINS THE EVOLUTION OF THE FOOTPLATE GRADES AND THE HISTORY OF THEIR TRADE UNIONS AND THE STRUGGLES TO IMPROVE THEIR WORKING LIVES

Give every man what is his—the accurate price of what he has done and been—no more shall any complain, neither shall the

earth suffer any more."—THOMAS CARLYLE.

BRANCH SECRETARY

W. YOUNG YEARS 1891 -1905

(Footplate Seniority, c1871)

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

For he today sheds his blood with me shall be my brother; be never so vile.

William Shakespeare

SUB CONTRACTED ENGINE MEN

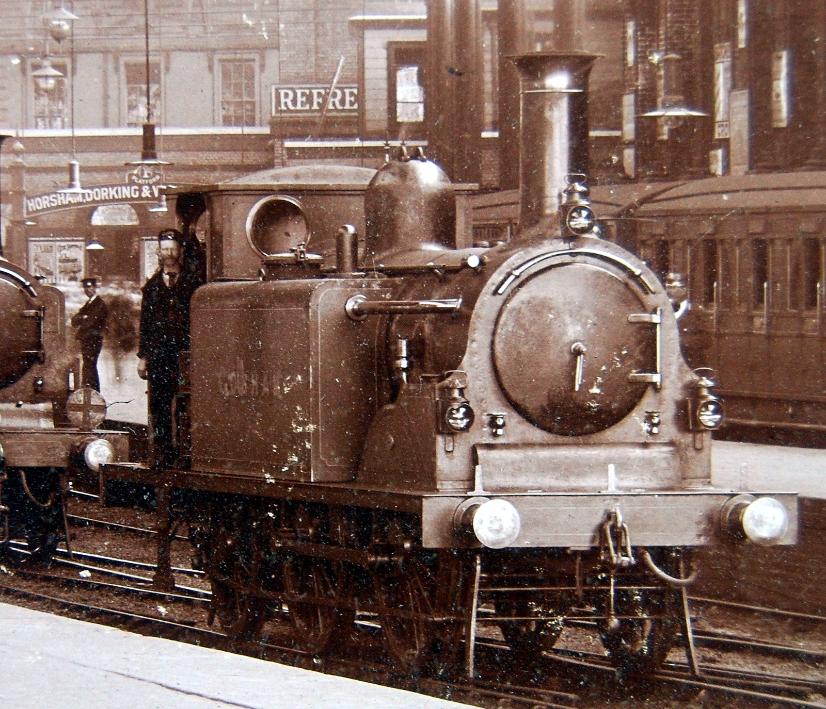

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Above Engine Driver H. Holbrook of New Cross (Gate) Loco Shed

Driver H. Holbrook was sub-contracted to to work D2 class No. 313 "PARIS" c1883 on the Grande & Petite Vitesse goods

train services between London & Newhaven Harbour. The Grande ran daily from Dieppe & the Petite three times weekly

from Caen. These services were mainly consisted of perishable traffic, such as seasonal fruit made up the greater part of

the loads, either from France or from merchant ships docking at Newhaven. Other engines drivers to work this engine up

until its withdrawal in 1905 were drivers (New Cross) Charles Churchill, Ned Oram, Alf Blackman and Harry Bowen.

Sub-contracting of Engine men and locomotives was also applied to the night continenatal boat train between London

Bridge and Newhaven. A driver employed under the contract arrangements would mean that the Company provided the

engine, coal, water and other stores, and paid the driver an agreed sum of money each month, out of which he had to pay

his fireman and cleaner. Hours of duty were not taken into account,and on many occassions in the winter months the crew

were twenty hours away from home. Sleep would, of course, be possible at Newhaven between trains.

This system originated when the harbour at Newhaven was tidal and the returned (up) services ran irregular, and was

still based on tidal workings, which meant the steamers would have to dock at various times subject to the tide at

Newhaven. To ensure a engine and crew was available for this duty when required, the driver was paid by contract. With

the deepening of the harbour and the construction of a new quay in the 1890's the tidal service ceased, but nevertheless

the "Grande Vitesse" contract remained in force for another 14 years, until 1905. The tittle of this train disappeared from

the public time tables, but lived on in the Central Section of the Southern Railway, working time tables until long after the

Second World War

As the load varied greatly according to the season, the premium was not so easily earned as it was with some of the boat

expresses, and Driver H. Holbrook regularly petitioned the directors for improved terms. In May, 1893 he complained that

his engine No. 313 'Paris' was burning 34 to 35lb. of coal per mile, including lighting up, and that so little time was

available at New Cross for cleaning that this often had to be undertaken by the fireman at Newhaven. On another

occasion Driver H. Holbrook made known his feeling concerning the substitute engine while his engine was under repair

at Brighton. In December, 1895 the "Grande Vitesse" timings were completely altered and the down train combined

carriages for Eastbourne, and at long last the contract was re-negotiated.

A regular loco used was B2 class engine No.325, Abergaveny with its Driver J. Turnball c1877 (New Cross) and in 1888

this engine was replaced by a Gladstone Class No. 195 "Cardew" in c1888 and her first driver George Gore. This

arrangement survived a little while after the steamers started to operate to a regular schedule.

The engine drivers at the country locomotive sheds were generally worked to a contract. Four men, a Driver, Driver-

Fireman, Fireman and a Cleaner worked in a squad and shared the contract price in definite proportions, for example, 5 :

5 : 3½ : 2.

Does anybody have any further information regarding the sub-contracting of footplate staff?

STORIES FROM THE SHOVEL

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

FACING TO THE ELEMENTS

HAND IN FRONT OF YOUR FACE

Fog proved troublesome for Brighton driver William Muzzle and his engine No. 210 ‘Cornwall’ on the evening of 10th

December, 1890, when at the head of the 5.40 p.m. Brighton and Eastbourne express, which was formed of sixteen vehicles,

including Pullman ‘Albert Edward’, Victoria was left sixteen minutes late owing to delays in collecting the rolling stock from

the sidings, and a further twenty four minutes were lost by the time Purley was reached, due to signal stops, cautious running,

and delays at Clapham and Croydon stations. There, visibility improved and with clear road the driver was encouraged to

increase speed until approaching Stoats Nest the train was travelling at fully 45 to 50 m.p.h. Suddenly a goods wagon was

seen standing on the line ahead, and it was too late for braking, so with little slackening of speed the crash came. No.210 and

the first seven carriages left the more-or-less track, but fortunately remained upright, and, although some 185 yards were

travelled in this manner, only eighteen persons complained of injury. Both William Muzzle and his fireman George Breach,

had a particularly luck escape, since not only did they survive the collision, but also avoided harm when the washout plug was

knocked from the firebox and scalding steam enveloped the footplate. The wagon had been accidently left on the main line

during shunting operations and had not been noticed in the darkness, despite a relief signalman having passed within ten

yards en route to the box.

STORIES FROM THE SHOVEL

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

LET IT SNOW.........LET IT SNOW

The winter of 1890-91 contained some of the worse weather on record in the Southern England, and on the night of Monday,

9th March, 1891 much of England was swept by a blizzard but the ‘Night Boat’ was not seriously impeded until south of

Merstham. Then much drifting by the high wind caused a 29 minute late arrival at Lewes, while at Southerham Junction the

signalman stopped the train and warned the crew that all signals ahead were inoperative. Proceeding at about 15 m.p.h.

through deepening snow, a 'Gladstone Class' loco No. 195 ‘Cardew’ struggled on to within a mile of Newhaven Town station

and then stuck fast until dug out the following morning. About two hundred yards behind the an old Craven engine 0-6-0 No.

394 with a goods also become embedded, which was just as well as since in such visibility the crew would have had little

chance of seeing the guard’s van’s red light.

A 'Craven Standard Goods Loco' no. 211 worked the 2.30 p.m. goods from New Cross to Lewes. It snowed hard all the way,

and on reaching Lewes and depositing their train, the crew found to their dismay a special goods of twenty-three wagons and

two brake vans awaiting transit to Newhaven. By this time the snow was drifting badly before a westerly gale and most signals

were unreliable if not out of action. However a start was made with both men finding such shelter as possible behind the

weather board. Little could be seen even at about 10 m.p.h. but despite this steady progress was made until they became

embedded up to the chimney base in a deep drift. Realising nothing more could be done, they flung out their fire and retired to

the guards van to spend the night. Next morning they were dug out about 9.30 a.m., when they found themselves only some

150 yards behind the Boat express. The gale blew so fiercely that many of the wagons had their tauplins ripped to pieces and

the guards van was only kept on the rails by the weight of snow to leeward.

Footplate Crew's Depot not known

FRACTURE TYRE AT EAST CROYDON

20th MARCH 1893

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

On the 20th March, 1893, a 'Gladstone Class' engine No.219 Cleveland got into trouble, when she was passing South

Croydon at 60 m.p.h. with the 8.40 a.m. Brighton – London bridge non-stop Pullman express. The train consisted of ten

coaches, plus Pullmans Maud & Jupiter, and weighed 260 tons empty. The journey had been uneventful, apart from a belt of

fog near Horley, until the electric communication bell was rung by the Conductor of Maud as South Croydon station was

approached. Looking back the driver noticed rising dust from the Pullmans, and immediately applied the brakes and flung the

engine in reverse. A very ragged stop was made at the southern end of East Croydon station, when an inspection disclosed

that Jupiter’s right tyre of the rear bogie had fractured and broken fifty three chairs. Only five windows were smashed or

cracked, and on one was injured, although Cleveland could not be moved until the fitters had attended to the jammed brakes

and badly damaged brake rodding. At the inquiry the tyres on Jupiter were found too thin and below Brighton standards

owning to the Company’s examiner being unfamiliar with their design, which was of Midland Railway pattern and unlike

those employed on the Brighton stock. Orders were immediately given for substitution of standard pattern tyres on all

Pullmans before entering regular traffic. Attempts to obtain payment from the Pullman Car Company were without success,

pursued for over twelve months.

REDUCING THE HOURS FOR FOOTPLATEMEN ON GOODS ENGINES

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the L.B.S.C.R.

Footplatemen have always worked long hours, this being especially so for the footplatemen who worked on goods engines,

who frequently spent sixteen or seventeen hours per day away from home, occasionally much longer when bad weather

delayed their trains. The Board of Trade considered that men working such long hours were the cause of many accidents and

in November 1893, broached the subject with the London & Brighton Railway's Chairman, who later instructed his

Locomotive Superintendent, Robert Billinton, to rearrange the goods rosters to provide each crew with a weekly rest day, and

to reduce the time spent on duty to fourteen hours per day. Robert Billinton made the necessary adjustments to the working

timetables, but because the London & Brighton Locomotive Committee refused to sanction the sharing of engines, he was

forced to purchase eight more locomotives to cover the goods traffic.

MORE PROBLEMS AT EAST CROYDON

31st AUGUST 1895

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the L.B.S.C.R.

On the evening of 31st August 1895, 'Gladstone Class' Loco No. 217 Northcote. It was heading the 5.05 p.m. London Bridge -

Eastbourne express, which include portions for Worthing, and East Grinstead, and consisting of fourteen vehicles. When

approaching East Croydon station at about 45 m.p.h., ten carriages suddenly left the rails at the V-crossing between the up

and down main the end of the lines in front of Croydon North signal box. Eleven passengers and two guards were injured. At

the inquiry it was found that the light brake van at the end of the Eastbourne portion had jumped the lines at this point

because of oscillation set up by the neighbouring heavier vehicles and the unevenness of the cross over. It dragged the

Worthing and East Grinstead portions off the track, but fortunately all these carriages remained upright.

COLLISION AT HAYWARDS HEATH

24th SEPTEMBER 1895

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

On the 24th September 1895, a 'Gladstone Class' engine No. 218 Beaconsfield was passing through Haywards Heath with the

3.22 p.m.Victoria – Eastbourne Pullman express and came into collision with an empty goods truck at 50 to 55 m.p.h. This

vehicle had just been thrown across the down main line by a 'D1' Class engine No.232 'Lewes', but no serious attempt was

made by the staff to warn the express train, which fortunately brushed the obstruction aside and remained on the track,

although every carriage and the Pullman car ‘Alexandra’ received damage.

GRAHAM FINLEY COLLECTION

Brighton Driver Harry “The Captain” Finley, with his son Reginal Albert Taylor.

LOCOMOTIVE JOURNAL 1898

Sir,-- In connection with the recent concessions granted

by the L. B. & S. C. Railway through our overtures I

beg to claim the indulgence of publicity to the jealous -

unmanly - and slanderous statements put forward in the

R.R. - that the deputation of which waited on Sir Allen

Sarle was of a purely personal character and had no

official basis. That, of course, is a direct lie, as we

never waited upon Sir Allen Sarle. Had the report been

confined to the R.R. there would have been no need of

replying to it, but the statements have been circulated,

and have excited comment, hence my desire to deny

such wilful misrepresentations. You know, Mr. Editor,

that Mr. W. Young, Brighton, Mr. J. Pogmore, New

Cross, and myself Battersea, were elected by the

members and approved by our E. C., and you, being

the chairman of a large open meeting when I gave the

report of an interview with our superintendent, I the

got a unanimous vote of confidence. A newspaper

supported by railwaymen, and guilty of such spiteful

vapourings, should be treated, as it deserves, with

contempt by the enginemen and firemen of the whole

country. Wishing you and the whole your readers a

Happy New Year.

Yours Fraternally

J. M. Bliss

BATTERSEA BRANCH

E.C. Member 1906 - 1903

A ROYAL PERFORMANCE

NATIONAL ARCHIVE COLLECTION

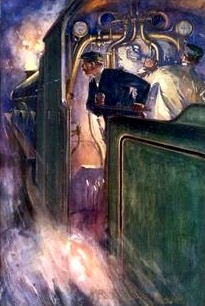

On the footplate of Empress, Driver Walter Cooper and his Fireman F.W. Way.

Queen Victoria died on 22nd January 1901. On Friday 1st February, her coffin was taken on board the Royal Yacht, Victoria and Albert for the passage across the Solent to the Royal Clarence Yard, Gosport. On the day of her funeral, Saturday 2nd February, Victoria station, was closed to the public and ordinary traffic between 9 a.m. and 11 p.m. in preparation for receiving the royal train, the advertisement and placards were removed and parts of the station structure cleaned up. The journey was to begin on the L.S.W.R. with the train being attached to a Brighton locomotive at Fareham.

Operating difficulties caused the carriages of King Edward’s L.B.S.C.R. train to be reversed into the platform and, according to the prepared seating plan; the coaches were the wrong way around. This was much to the annoyance of the royal and distinguished mourners, including the Kaiser.

There was a delay on changing the engines at Fareham with Brighton ‘B4 class 4-4-0 No. 54 Empress’, coming on to the train. The pilot engine, also a ‘B4, No. 53 Sidar’, was sent off in advance. By the time the funeral train was ready a further two minutes had been lost.

On the footplate of the train engine were L.B.S.C.R. Locomotive Superintendent, R.J. Billinton, with his Outdoor Locomotive Superintendent, J. Richardson, Driver Walter Cooper and Fireman F.W. Way. Richardson told Driver Cooper that for heaven’s sake he was to make up some time at all cost as the new King would be livid if kept waiting at Victoria.

The old Queen had always insisted that no train in which she travelled should ever exceed 40 m.p.h. Driver Cooper did as instructed and the Queen’s remains found themselves travelling at 80 m.p.h. on the flat between Havant and Ford. To Victoria, a top speed of 92 m.p.h. was then reached down Holmwood bank. With such speeds, quite unbecoming for the ultimate Victorian funeral, the train reached Victoria station two minutes early. The German Kaiser was so delighted with the high speed journey that he sent an equerry to congratulate the Driver and Fireman. The King was, at point, none the wiser and completely unruffled. This was not to last.

From Victoria station, the coffin was conveyed on a gun-carriage through London to Paddington Station for the last stage of the journey to Windsor. Before departure of the train, the King was heard to say to the emperor, ‘come along, hurry up we are 20 minutes late!’ On arrival at Windsor the hawsers provided to haul the gun-carriage frozen up and the horses had become restive in the intense cold. Communication cords had to be taken from berthed G.W.R. coaches to enable seamen to haul the gun-carriage.

Extracted from the book

Going of the rails

LOCOMOTIVE WORKING ON SUSSEX BRANCH LINES 1902

EXTRACTED AND ADAPTED THE JOHN PELHAM MAINLAND

FROM RAILWAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1902

At the beginning of the century, the working of the locomotive depots at Littlehampton, Bognor, and Midhurst exhibit many

interesting features directly traceable to mid -Victorian practice. These depots were included in the Horsham Locomotive

District; Midhurst and Littlehampton had four engines each, and Bognor two engines. At least one engine at each shed was

designates the “Branch Engine,” a relic of the practice established by John Chester Craven, Locomotive Superintendent of

the L.B.S.C.R. from 1852 to 1869.

The Locomotive Foreman at Horsham made a tour of his District on the last Wednesday of each month. Leaving Horsham at

10.20 a.m. the circuit of inspection occupied no less than 7 1/2 hours, unless as sometimes happened, Bognor was omitted on

a verbal assurance being given by the fitter in charge at Littlehampton that “they were all right there”; this reduced the time

by 2 1/2 hours.

The choice of the day was a relic of the past; it had been originated with an old instruction which held the foreman personally

responsible for certifying that the reserve coal stack had not vanished in whole or in part, and that the oil stock was according

to the books, and had not been diverted to other purposes. Occasionally, on the second Wednesday of the month, the foreman

paid a visit to Littlehampton only, but this was an exceptional measure of supervision. The reason for the choice of Wednesday

was that on this day the Outdoor Locomotive Superintendent regularly visited the Chief Offices at London Bridge and

therefore was not likely to descend upon Horsham, and find the Foreman absent.

For all practical purposes the telephone was non-existent, the only means of communication, other than by rail-borne letter,

being the single needle telegraph, known as the “speaking instrument.”

The immediate responsibility for these out-depots therefore rested upon the man in charge of the shed, and sol on as he was

conscientious in the discharge of his in charge of the shed, and so long as he was conscientious in the discharge of his duties,

everything worked satisfactorily. The standard of locomotive maintenance at these depots compared favourably with any other

shed on the system, the mileage run between shop repairs averaging 65,000 in a period of about 2 3/4 years. The general

arrangements were primitive by modern standards, but were suited to the conditions of railway working at that time.

Variations of the standard engine workings, as diagrammed, were confined to local adjustment at the time of the annual

revisions of the timetables, and at holiday times, when late running of the London - Portsmouth trains resulted in unscheduled

trips on the Bognor and Littlehampton branches. During the Goodwood Race period (the week before the August Bank

Holiday) some slight adjustments were made to the train service on the Midhurst branch.

All clerical and administrative work was done at Horsham, as were repairs which could not be carried out by the fitter

stationed at Littlehampton. The sole boilermaker visited the out depots if necessary, but such occasions were exceptional,

engines being worked up to Horsham on suitable duties and charged over as required. Additional personnel, other than

repairs staff, were provided from Horsham to cover sickness, leave, and other similar contingencies, as well as for special

traffic requirements. Engine power for the latter was usually supplied from Horsham as well. In practice, if any member of the

staff fell sick, provisional arrangements to cover his duties had to be made by the local man in charge of the depot until a

substitute could be produced from Horsham, which ordinary was not until the following day. That life on the railway was

much less strenuous for the fact that Horsham was not frequently troubled by such applications.

When a vacancy at any of the four depots occurred, it was filled by the senior man in the junior grade in the district, unless he

expressed his desire not to do so, in which case the offer went to the next senior and so on. In the event of the post of fitter-in-

charge at Littlehampton becoming vacant, the appointment was made but the Outdoor Locomotive Superintendent, Brighton.

The shed at Littlehampton, in which four tank engines could just be accommodated, and locomotives enthusiasts could obtain

close up views of the engines from the public highway. There was consequently no occasion for any contravention of the law

of trespass, or fear of prosecution for loitering such as was the case at Bognor and Midhurst. Nevertheless, warning notices

exhibited on the Company’s premises against loitering and trespassing were so numerous and conspicuous as to suggest to

visitor that the local inhabitants possessed a particular flair for such offences, but the present writer knows of no case in

which it was necessary to summon assistance from the Police Station immediately opposite the shed.

At Littlehampton, the fitter was in charge, and during the daytime he usually was to be found there, except on Mondays and

Wednesdays, when he visited Bognor and Midhurst respectively to carryout repairs to the engine stationed there.Having but

ten engines to look after (a small number for those days) the post was considered to be an easy one, as it undoubtedly was if

action was taken to forestall mechanical troubles.

As Littlehampton possessed direct rail access from theBrighton, London and Portsmouth directions, it never partook of remote

character associated with Bognor and Midhurst, and engines stationed there were more generally visible, as they has a much

less restricted range of operation. The Littlehampton goods engine worked from that station to Brighton via the Preston Park

spur on Monday to Friday nights inclusive, the enginemen being on duty 12 hours a night, thus completing their 60 hour week

in five night. It was washed out by the pump-man on Monday mornings. The “ local service engine,” a Stroudley 0-4-2 tank in

1900, worked a turn daily as far as Three Bridges and back. This engine, and the branch engine, were washed out regularly

after six days’ worked by the pump-man (but not on a Monday) the spare engine being used to cover their normal duties on

such occasions.

The Bognor branch engine, a “Terrier” tank, was washed out regularly every Monday, the spare engine (another “Terrier”)

being used only on such occasions. The latter was generally a run-down specimen waiting it turn for general repairs in the

shops. On other days it reposed behind closed doors in the combined running shed and pumping station, the site of which is

now in the centre of the main tracks, approximately half-way between the end of the platforms and the Bersted level crossing.

Its isolation rendered a clandestine visit a matter of some difficulty, but a persistent oral tradition records that marathon one

enthusiast awaited in ambush the hour (about midday) when the pump-man) adjourned to a certain establishment in the

immediate vicinity (to wit, the “Richmond Arms”) to enter the well guarded area and behold the rara avis ensconced therein.

As the write confesses to having acted similarly at Midhurst in 1901, he is prepared to accept the Bognor tradition as

possessing at least, some foundation in fact.

The clearer worked, of course, at nights. He had to coal and light up the engine, as well as clean it, for the next day’s work,

which commenced with a light run to Barnham to “bring in the goods” from that station at about 6.30 a.m. The last trip out

and back left Bognor about 9.40 p.m., to connect with coastal services, after which the branch closed for the night. The shed

was in charge of a driver who worked early and late shift alternatively, but performed only about 7 1/2 hours as a driver, the

balance of 2 1/2 hours being supposed to be devoted to administrative duties. The latter mainly consisted in sending up to

Horsham the drivers’ journals (total two) the records of the daily coal and oil issues (about 30 c.w.t. and 4 pints respectively)

and some other particulars of like character, all of which could easily be discharged in about 20 minutes.

Of the three depots, Bognor was the most primitive and the most isolated, as there was no facing connection with the main line

at Barnham. The branch line was single, worked on the staff and ticket principle, the tickets only coming into use on occasions

in the summer when excursions mainly school treats arrived from a distance. These trains had, of course, to shunt on and off

the branch at Barnham. The enginemen and guards booked off and on again for the return journey, unless there was any

major defect on the engine, in which case it had to worked light to Brighton to obtain another for the up trip. Strange to say,

this procedure was of the rarest occurrence. It is not recorded what happened if a Stroudley “Single” or a Class “B2” 4-4-0

showed signs of shortage of water in the boiler, but it is to be presumed that the pump-man “made the necessary

arrangements” as there was no one else to do so.

The Midhurst branch passenger service required two “Terrier” tank engines to be provided from that depot daily, a third

engine being held as spare to cover washing out and repairs. It was not until after the turn of the century that the first “D”

Class 0-4-2 tank arrived to displace one of the “Terriers.” Some few years elapsed before the “Terriers” finally disappeared

from this shed.

The goods engine worked a trip from Midhurst to Three Bridges every week night, but on Sunday mornings it arrived back

somewhat earlier than on other days. The engine as washed out on Monday mornings. At one time this engine worked an

occasional ballast trip from Midhurst to Beddington Lane (Croydon) and back during the daytime. The shed administration

was on similar lines to that at Bognor, except that the pump-man and not one of the drivers was in charge.

The replacement of the “Terrier” tanks by “D” Class 0-4-2s on the regular branch line duties was necessitated by the

substitution of six wheel main line stock for the five coach four wheel sets previously used, which entailed an increase in the

tare weight of nearly 90 per cent. per passenger. The change had been completed by 1906. At Bognor, however , a “Terrier”

continued to beheld occasionally for working that branch to be held as a spare engine until 1919. It was used occasionally for

working that brach , and on the Littlehampton branch, when the necessity arose.

* John Pelham Maitland, was a Loco Foreman at Newhaven & Littlehampton loco sheds.

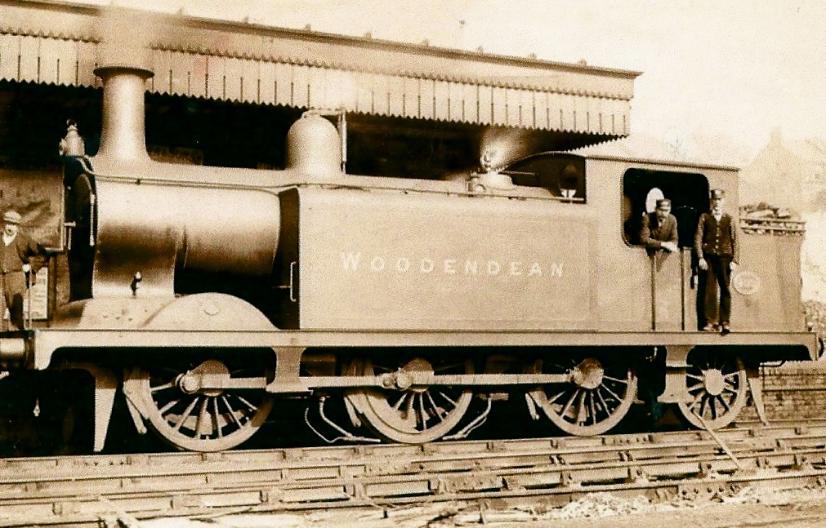

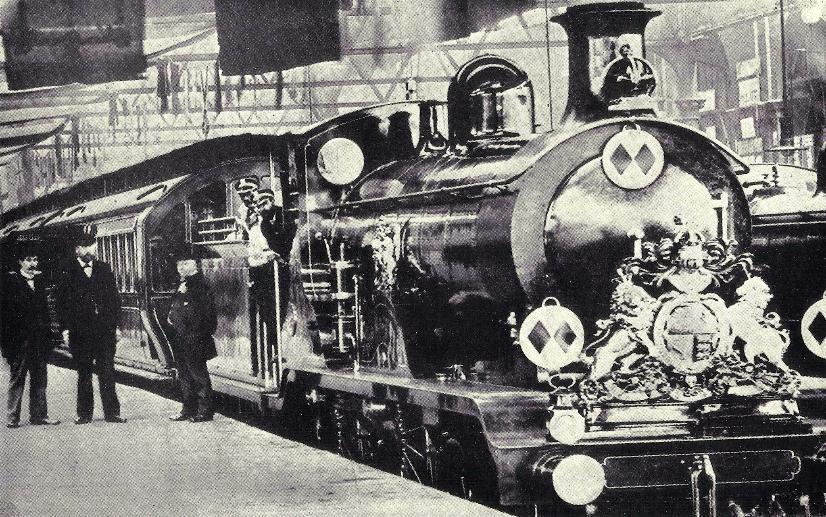

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Brighton Royal Train Driver John Pullen, and his fireman, both wearing their Royal Train Helmets, whilst standing at

Victoria station with their locomotive Class H1 No 42 "His Majesty" in August 1902.

Standing on the platform with his back to the locomotive is Locomotive Superintendent Robert Billinton and second from left

is Outdoor Locomotive Superintendent, John James Richardson.

*It was from John Richardson initiative that the use of “White Coal” in connection with Royal trains originated. The trans

were made so dirty by coal dust that he conceived the idea of white-washing the coal. The “White Coal” on the tender caused

amusement, but proved efficacious.

John Richardson retired on the 1st January, 1916, after served the London Brighton & South coast Railway Company for 48

years. At the time he was the oldest railway servant in the United Kingdom.

* Extracted from the Sussex Express, 31st December 1915.

Triennial Conference of May 1903

It was agreed that Engine Cleaners and Electric Motormen were all allowed to join A.S.L.E.&F.

and the establishing of a Political Fund.

LONDON - BRIGHTON SPEED RECORD OF 26th JULY 1903

BY DRIVER JOHN THOMPSETT

extracted and adapted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

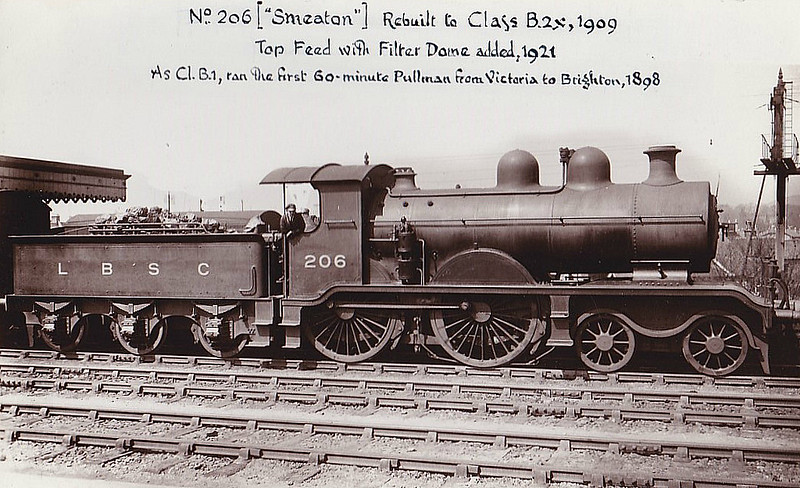

POSTCARD

On 2nd October, 1898 the Sunday ‘Pullman Limited’ commenced operating and by the turn of the century name of the train

was called ‘Brighton Limited’. At this period the L.B. & S.C.R. was anxious to clear itself of its long-standing reputation for

dilatoriness, caused partly by traffic congestion on the main line north of Redhill, and some very fast runs were made with the

lightly loaded Pullman Limited on Sundays, when the track was relatively clear. This train was timed to cover the 50 ¾ miles

between Victoria and Brighton in each direction in exactly sixty minutes, and in the coming years the new engines could cut

several minutes of the schedule.

On the 21st December 1901, a speed ran with the down express to Brighton, with a Billinton B4 Class No. 70 'Holyrood,' in

53 minutes and 49 seconds at an average speed of 57 ¼ m.p.h. while on Christmas Day of that year, another B4 Class, No. 68

'Malborough,' completed the same journey in 51 minutes 11 seconds with a maximum speed of 88 m.p.h. near Horley.

This, however, was but a foretaste of what these engines could really do when given their head. About this time there were

proposals in the air for a rival electrified line to Brighton, coupled with the specious promise of fifty miles in fifty minutes, and

the L.B. & S.C.R. decided to show that whatever electricity could do, steam could do better.

On 26th July,1903, Brighton Driver John Thompsett, with his engine, B4 Class, No. 70 ‘Holyrood,’ a specially light version of

the Pullman Limited was prepared, consisting of three eight-wheeled cars and a brake van, making up a total weight of about

130 tons, run the fastest ever return journey between London and Brighton. This engine had established a reputation for fast

running and was chosen for the task, the train being ‘Limited,’ which for the occasion had accommodation curtailed to only

three Pullmans and a van. The road was specially cleared from Victoria to Brighton, and Driver Thompsett given a free hand

to make the best time possible, provided all the Company’s speed restrictions were adhered to, and no unnecessary risks taken.

Brighton was reached in 48 minutes 41 seconds at an average speed of 62 ½ m.p.h a time, and a maximum speed of 90 miles

an hour near Horley, and was never equaled in the subsequent history of the L.B. & S.C.R.

In the evening the same engine and crew raced the train back to Victoria in 50 minutes 21 seconds, with an average of 60.8

miles an hour and a maximum of 85 miles an hour, and again a record for the Brighton line. Although worthy of the highest

praise and forming first-rate advertising could not be indulged in daily without seriously disrupting all other services. There

the L.B. & S.C.R. Directors and Robert Billinton, having shown the world what the Brighton could do, very wisely made no

attempt to introduce 60 m.ph. services, although a blind eye was turned on those drivers who wish to reduce the schedules by

three or four minutes. As in all other runs the second up journey, Driver John Thompsett did not know that he was being

timed.

Having shown their paces with these specially prepared runs, the L.B. & S.C.R. felt that such times were not beyond the scope

of ordinary traffic conditions. On Sunday, June 30th, 1907, the new Marsh Atlantic No. 37 ran the Pullman Limited from

Victoria to Brighton in 51 minutes 48 seconds. The train consisted of five eight-wheeled cars, two twelve-wheelers, and two

six-wheeled vans. This was in comparison an even better performance than Holyrood's record run of 26th July, 1903, since it

was made under ordinary traffic conditions, with several checks near Earlswood owing to road widening, and a train of

nearly double the weight. By this time, however, the rival electric schemes had faded away and the L.B. & S.C.R. settled down

to its normal sixty minute schedule.

1903 Brighton drivers designated Brighton Gladstone Class locomotives. which included

Driver Taylor was in charge of No. 193 ‘Freemantle’

Driver Parker, was in charge of No. 184 ‘Carew D. Gilbert’

Driver Sharman was in charge of No.181 ‘Eastbourne’

Driver Wright was in charge of No. 190 ‘Arthur Otway.’

Driver John Thompsett, was in charge of B4 Class, No. 70 ‘Holyrood,’

Charlie Peters was an inspector and a designated trial driver, and was responsible for preparing all the new heavily repaired

engines for the road. He also had to take these engines out on trial runs, usually to West Worthing or Littlehampton, as they

came out of the shops.

LONDON BRIGHTON &

SOUTH COAST RAILWAY

1904

Number of Enginemen within the L.B.& S.C.R. 630

(including Motormen)

Wages for Enginemen: 34 - 48 Shillings per week, working

day 10 hours and Promotion according to needs of service.

Wages for Firemen; 21 -27 per week, working day 10 hours

and Promotion after six years firing service.

ASLEF COLLECTION

THE BRIGHTON BRANCH OF A.S.L.E.&F. WEBSITE.

HAS NOW BEEN MOVED TO A NEW SITE CALLED

IGNITING THE FLAMING OF UNITY

https://ignitingtheflameofunity.yolasite.com/

PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW

TO TRANSFER TO THIS NEW SITE

CLICK ON THE ABOVE IMAGE TO TAKE YOU

TO THE NEW UPDATED COMBINED AND WEBSITE

IGNITING THE FLAME OF UNITY WEBSITE

https://ignitingtheflameofunity.yolasite.com/

THIS WEBSITE COMBINES THE FOLLOWING WEBSITES

THE BRIGHTON A.S.L.E.&F., THE BRIGHTON MOTIVE POWER DEPOTS

& THE SUSSEX MOTIVE POWER WEBSITES

WHICH EXPLAINS THE EVOLUTION OF THE FOOTPLATE GRADES AND THE

HISTORY OF THEIR TRADE UNIONS AND THE STRUGGLES TO IMPROVE

THEIR WORKING LIVES

CLICK ON THE ABOVE IMAGE TO TAKE YOU

TO THE NEW UPDATED COMBINED AND WEBSITE

IGNITING THE FLAME OF UNITY WEBSITE

https://ignitingtheflameofunity.yolasite.com/

THIS WEBSITE COMBINES THE FOLLOWING WEBSITES

THE BRIGHTON A.S.L.E.&F., THE BRIGHTON MOTIVE POWER DEPOTS

& THE SUSSEX MOTIVE POWER WEBSITES

WHICH EXPLAINS THE EVOLUTION OF THE FOOTPLATE GRADES AND THE

HISTORY OF THEIR TRADE UNIONS AND THE STRUGGLES TO IMPROVE

THEIR WORKING LIVES